(ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED IN PLANT SERVICES – ONLINE)

The heating, ventilation and air-conditioning (HVAC) system is the respiratory system – the lungs – of a building. Return ducts take in air from the occupied space and send it through an air handler, where it is warmed or cooled and returned to the occupied space through a network of supply ducts. A well-maintained system removes the stale gases and provides a steady stream of oxygen-rich, comfortable, odorless air for the occupants. But where there’s air, there’s particulate.

Why be particular about particulate?

According to the Air Quality Management District near Los Angeles, an average [i]cubic inch[i] of local urban air contains about 250,000 particles. This reduces to 25,000 to 50,000 particles near the coast and increases to a million or more near highways. Even a cubic inch of the purest air at mountain peaks and over the center of the ocean holds thousands of particles.

With the rise of nanotechnology, the primary focus in the medical world has been on ultrafine particles known as PM2.5 – particulate matter with a size of 2.5 microns and smaller. These aren’t good for one’s health. High exposure to PM2.5 and larger particles has been linked to an astonishing array of physical ailments, including:

- Strokes (Annals of Neurology)

- Blood clots in leg veins (Archives of Internal Medicine)

- Wheezing in infants (Thorax)

- Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s (Environmental Factor)

- Clogged arteries (Genome Biology)

- Heart risks in young adults (American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine)

- Premature birth (American Journal of Epidemiology online)

- Premature death (Thorax online)

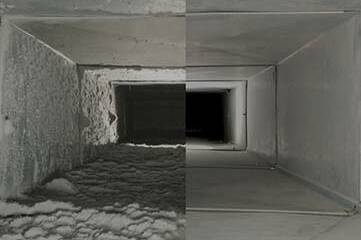

As air is drawn through an HVAC system, particulates gradually begin to collect on the interior of the ductwork, fan, fan housing, coils and other parts in contact with the air stream. As time goes on, the particles can coat the surfaces to a thickness of 3 in. or more. Although contaminant buildup usually isn’t more than 0.5 in. deep, sometimes it can be several inches. A 2-in. build-up on the bottom of a 12 in. x 12 in. duct makes it a 10 in. x 12 in. duct. This narrowing of the flow area produces more resistance to air going through, adding to the energy bill. A Japanese study in the 1980s, however, found that when the contaminant coating thickness reaches 0.03 in., the particulates start to peel off and reenter the air stream.

HVAC systems get dirty over time, but at variable rates. Contaminant accumulation rates and peel-off rates are determined by a variety of factors, including duct size, air speed, air volume, particulate load in the air and particulate size. Some systems accumulate large amounts of debris and some reach a point of near equilibrium, where the rate of accumulation is only slightly higher than the rate of peel-off.

Energy costs

One of the first things to be affected by particulate build-up is energy cost, particularly from the heating and cooling coils. The American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air-Conditioning Engineers (ASHRAE) found that simply cleaning the coils after a year of use produced a considerable energy savings by increasing the cfm by 14% and by improving heat-transfer ability by 10-25% (ASHRAE Journal, November 2006).

But many plants allow their HVAC systems to go years without a good coil cleaning, so it seems reasonable to conclude that industry is missing out on greater energy savings. As time goes on, accumulation on other parts of the system adds to the energy loss.

Some fan blades are slightly cupped to make them aerodynamic. Accumulated dirt alters the fan-blade profile to render them less efficient and they pull fewer cfm. Also, dirt adds weight to the fan, so more energy is required to turn it. A clean fan is cheaper to run. Turning vanes at duct elbows collect particulate matter and all manner of debris over time. I’ve seen cardboard, pieces of insulation and dead birds clogging the elbows.

Clogged registers also introduce inefficiencies. Besides particulate buildup, after five, 10 or 20 years, a lot of foreign objects can find their way into an HVAC system and get caught behind the registers. Because air flow can be restricted in so many ways by particulate buildup, a cleaning can cause a dramatic increase in cfm, particularly in older systems that have never been cleaned.

Preventive measures

You have control over the rate of dirt accumulation in your HVAC system. The following items are the primary contributors to system contamination and efficiency loss:

- Missing filters – not common, but it makes a system dirtier faster

- Filters poorly fitted or with gaps between them

- Improper filters – use those recommended by the OEM

- Dirty filters and failure to clean the filter rack when changing filters

- Neglecting the air handler – not inspecting periodically to spot functional problems

- Dirty operating environment

- Duct leakage – gaps at duct joints, where unfiltered air can be drawn in

- Poor or no condensate drainage in the air handler

- Deteriorated fiberglass liner – friable, small or large pieces get into the ductwork

- Leaks in air handlers – worn door seals or holes in the cabinets

Monitor the symptoms

Unless you’re in a clean environment, such as a hospital, where HVAC cleaning is part of routine maintenance, you might wonder how to make an educated decision on when to clean a system. Here are some basic guidelines.

1. Replacing or repairing the air handler. When you change a fan, fan motor or the entire air handler, you shake the duct system and loosen the dirt inside it. A new fan likely will blow greater cfm than the old one, giving it enough strength to blast out lots of particulates that would have otherwise remained attached.

2. A poorly maintained HVAC system. If the filters have been missing or poorly fitted for six months or more, the likelihood is that the fan, coils and ductwork are laden with particulates and debris. A cleaning likely will be needed to give you healthy air output and coils that aren’t clogged.

3. Mold growth. This is more common in the South, but can be a problem anywhere. Biological growth inside the air handler can emit foul odors and can even make people sick. Mold growth inside the ductwork is less likely, but it can occur. Get mold contamination corrected immediately because failure to remedy it could open your company up to legal consequences.

4. Dirt blowing out. If system contamination reaches the point where dirt is coming out, covering machinery, desks or an employee’s lunch, you’ve probably hit a point of no return. The only remedy is cleaning the HVAC system thoroughly. Before you make the call, ensure the problem isn’t caused by something simple, like missing filters or an open door on the air handler.

5. Bad smells. Cigarette smoke, industrial fumes, particulates, algae, fungi, mold – a number of things can settle into a duct system, causing a rank odor when the system is running. We’ve found that the return

ductwork is frequently the source of odors. It gets much dirtier than supply ductwork because it pulls in unfiltered air. Cleaning usually remedies this problem.

6. Dirty ducts or air handler. Sometimes you simply look at the system and common sense tells you it’s filthy and people shouldn’t be breathing air from it.

7. Air flow is restricted by dirt buildup. When enough particulates and debris collect in critical areas, it can cut air flow dramatically. Coils are a primary culprit because they have narrow air passages. These clog up quickly. Registers, particularly return registers with screen covers, also can become clogged.

8. Sick occupants. A dirty HVAC system isn’t responsible for every case of sick building syndrome, but it can be a contributor. A study conducted by Allergy Consumer Review (reported at www.allergyconsumerreview.com/air-purifiers-furnace-filters.html) found that HVAC cleaning reduced airborne particulates by about 75% and contributed significantly to a reduction of allergy and illness symptoms in the building.

9. New construction. It’s nearly impossible to keep construction dust from getting into the HVAC system. The architectural specs for many government buildings mandate a “post-construction blowout” (cleaning) before the system can be used.

There are no set standards regulating how often HVAC cleaning should be performed. For hospitals, which do it more than most facilities, every five to 10 years is common, although coil cleaning might be more frequent. It depends a great deal on how quickly the system gets dirty and the needs of the occupants. The primary factor concerns how often the system exhibits one of the symptoms listed above. Ideally, you want to clean the system before it turns into an emergency; however, coils should be cleaned annually to capture an easy and considerable cost savings.

The cleaning process

Duct cleaning technology has been refined over the years. In the 1980s, the National Air Duct Cleaners Association (NADCA) promulgated industry standards to promote greater professionalism. Today, most reputable duct-cleaning firms are certified NADCA members.

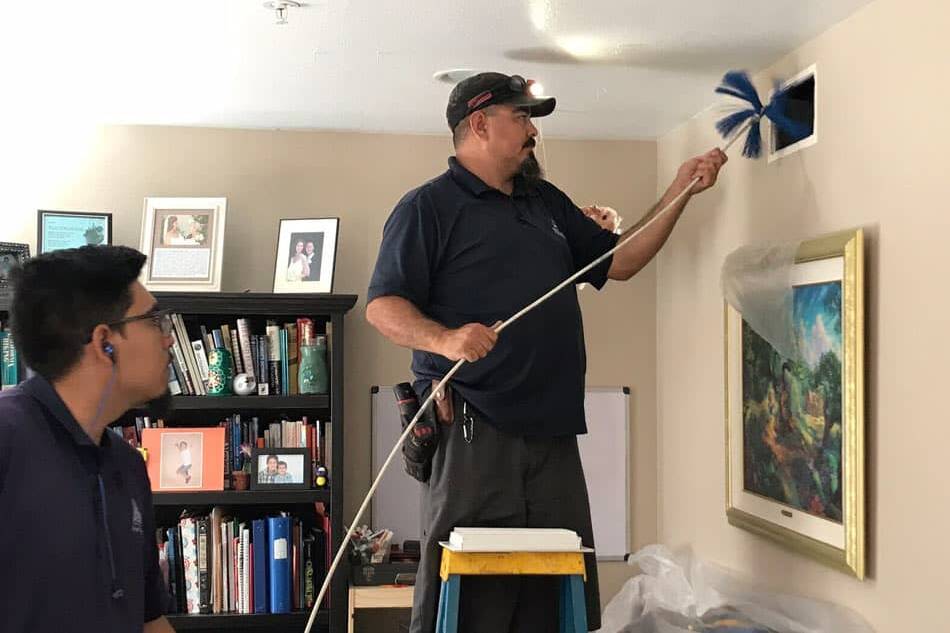

Duct cleaning is usually done during off hours, when operations are shut down, so cleaning contractors work nights and weekends. Duct-cleaning equipment varies by company and even by region, but there are two basic technologies: contact cleaning and negative-air cleaning. With either method, each part of the HVAC system gets cleaned, including the registers, coils, air hander and ductwork.

Contact cleaning is the old-school method. The ductwork is hand-vacuumed. If the ducts are large enough, a technician crawls the interior. If not, the ducts are cleaned by cutting access holes every 15 ft. or so, reaching in, and vacuuming. Contact cleaning is the most thorough method but, because it can be more labor intensive (and thus more costly), it’s not used very often. However, even on some modern jobs, part of the work might require contact cleaning.

Negative-air-cleaning technology has been developed during the last 20 years. It involves a large vacuum (known as a negative-air machine) attached to a duct opening to produce a powerful draw of air through a section of ductwork. A variety of tools can be run through the duct while the vacuum is operating. Hoses can blast air and augers (long cables with a spinning brush on the end) can agitate the particulate into the air stream for the negative-air machine to collect.

Regardless of approach, industry best practices say that it’s insufficient simply to connect a strong vacuum up to the duct. Some kind of contact agitation, such as air blasting or mechanical brushing, is required on the interior duct surfaces to remove particulates more effectively. NADCA standards also dictate that either method must use vacuum devices equipped with high efficiency particulate air (HEPA) filters that catch particles as small as 0.3 microns.

Design problems

Manufacturing processes can release oil mist, lint, sawdust and all manner of particulate matter into the air. Any HVAC system is at risk for contamination in such an environment, particularly if the return or intake registers draw air from the particulate-filled zone. Such contamination not only increases energy costs, but can be a fire hazard if the material is flammable.

Some industrial and commercial venues can exhibit serious HVAC contamination. This is particularly true if a system shares air with industrial processes that release airborne particulate matter. A classic example was a California hotel, where the HVAC system’s large fresh-air intake opening was just above a gigantic laundry exhaust vent. The HVAC system had to cool air that was 20°F hotter than normal outside air. Lint also clogged the filters and coils and caused rapid ductwork buildup.

The HVAC air intake register at a cooking facility was too close to the cooking area. Smoke from the cooking process – which includes minute droplets of grease and steam – was drawn into the HVAC system. Food odors came through the ductwork and grease accumulated on the coils, filters and ductwork. Cleaning this system was an arduous exercise.

The best advice for such situations is to design the system properly in the first place so it doesn’t cross-contaminate from the industrial process – primarily by not drawing from particulate-laden air. If you already have an HVAC system with a poor design, an HVAC engineer might be able to redesign the filtration or reroute the ductwork to solve the problem.

A quality HVAC system can be a luxury when it runs well with little attention. But, just like dependable old friends, they occasionally let us know they need a helping hand. When they become overloaded with particulate and debris, problems begin. HVAC cleaning is a well-established procedure for remedying a contaminated system. When done properly by a reputable company, it can improve air quality, restore system functionality and reduce the cost of running it.