(ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED IN LAUNDRY TODAY)

It’s one of the best kept secrets in Los Angeles. Years ago, in the middle of the night, a maintenance worker was brushing lint off the ceiling of a laundry room in one of L.A.’s most prestigious hotels. The man bumped a light bulb and broke the glass. In a flash the hot filament touched lint. A flame shot across the ceiling like a prairie fire and was sucked into an open exhaust shaft coated with lint. The shaft—designed to draw the hot, moist air of dryers out of the laundry—pulled the blaze more than ten stories through the center of the hotel.

Fortunately, the fire department arrived almost instantaneously. Hotel guests never knew. Neither did the media. The reputation of the city’s premier hotel was preserved.

But after that night, that laundry shaft was cleaned religiously.

All laundries have similar shafts or ductwork designed to vent their dryers’ moisture and hot air. Usually these start at the back of the dryers and combine into a common exhaust duct which takes the wet air out of the building.

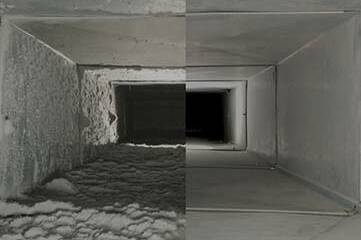

The inevitable result is the accumulation of lint inside this ductwork. How much lint? Here are some typical amounts:

A major hotel in California has a massive duct system that collects approximately 500 cubic feet of lint every six months.

Workers cleaning the laundry ducts of the 36-story, glass-tower Bonaventure Hotel in downtown Los Angeles pull out 20 55-gallon trash bags of lint every six months.

The ducts at the Los Angeles Police Department laundry produce about 18 55-gallon trash bags of lint twice a year.

For more than thirty years our company, headquartered in Los Angeles, has pulled lint from these ducts all over California—from Arnold Schwarzeneggar’s house to the hospital laundries to the region’s finest hotels.

Without regular cleaning, several problems arise. Fire risk is the most obvious. One well-known hotel had a dryer catch fire when solvent-soaked rags being dried released flammable vapors. Fortunately for the hotel, the ducts had been cleaned recently and the fire didn’t spread through the ventilation system.

Longer drying time is another consequence. Lint clogs ductwork, exhaust fans, and screens that may be at the end of the duct. This restricts the amount of moisture that can be discharged from dryers. Drying time can be doubled, tripled, or as we often hear, “It takes forever.” The energy waste is substantial.

A third reason for cleaning is to reduce mechanical and structural damage to the dryers. When the moisture can’t vent through the ductwork, it builds up in the dryer. Over time rust can eat away at components and the dryer shell.

The dryer’s mechanical parts are under greater stress when trying to push air through a lint-laden duct. Burners run longer, switches turn on and off more often. Burned-out thermostats are a common result in some situations.

The chief engineer of one major condominium complex in downtown Los Angeles knows it’s time to clean the ducts when “the airflow switch stops kicking in on Dryer Number One.” The switch is regulated by how much air can be pushed out by the dryer. When lint restricts the flow too much, the switch won’t function. The engineer knows from experience that Dryers Number Two and Three will soon follow.

There’s yet a fourth reason for keeping the ducts clean. These ducts often draw air from the laundry room as well as the dryers, keeping down temperature and lint accumulation in the work areas. Clogged ventilation can leave stagnant hot air and lint particles floating inside the laundry.

Terry Buchner, Chief Engineer for Beverly Hill’s beautiful Four Seasons Hotel was running a packed hotel, filled with guests, celebrities, and paparazzi attending the Academy Awards ceremonies when we interviewed him about his laundry ducts.

“The most important thing to us is our guests,” he said. “If we don’t keep the dryer ducts cleaned, drying time starts to take longer because we don’t have the right air flow. It starts a snowball effect. Soon we have trouble getting linens to the rooms on time. Then the maids run behind schedule on the room cleaning. It throws everything off. Our guests are too important to us to let that happen.

“Plus there’s the added cost of gas and electricity when drying time is extended. Then there’s the safety issue. One spark in the wrong place and you’d be amazed at how fast lint burns. With the duct running through the inside of the hotel, you just can’t let that happen.”

Chris Doyle is service manager of Consolidated Smart Systems (formerly Consolidated Lauco), which is estimated to be the second largest coin laundry service in California and the fourth largest in the U.S.

“When laundry ducts become clogged, they stop drawing,” he said. “Tenants stop using the machines because the clothes take too long to dry. We gauge the productivity of our machines by the number of people who use them per day. If that goes down due to clogged vents, we don’t make money.”

“We do intensive training on our guys,” he continued. “They learn to recognize signs like excessive lint behind dryers and clothes not drying. Lint absolutely builds up faster inside the dryer when the ducts are filled with buildup.”

Some laundry managers think they are safe from lint buildup in the ducts if they have a “wash-down system” in place. This is a device that runs dryer exhaust air through a mechanical waterfall to remove lint. While this helps reduce lint collection in the ducts, it does not necessarily prevent it. We clean a number of duct systems with wash-down devices, and the lint accumulation in the ductwork is substantial.

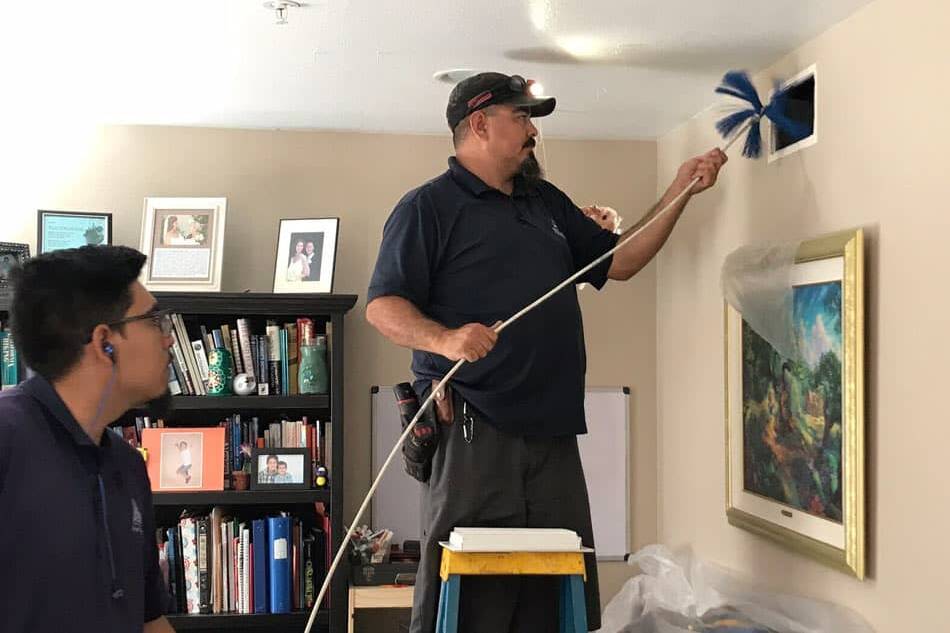

How is the cleaning done? Most ductwork has access doors where workmen can reach in or even climb in to remove the lint. Cleaning any connected fan or screens is usually part of the job.

The usual interval between cleanings is three to six months. This can be longer or shorter, depending on the laundry’s needs.

Getting the laundry ducts cleaned should be part of every laundry manager’s routine maintenance schedule. It lengthens the life of his equipment, reduces down time, and can even save lives.